Nile Miller came from Austin, Texas to the city of Kharkiv in eastern Ukraine as an exchange student. Little did he know when he arrived that he would witness a revolution during his time in the country. On MH he shares his views of a country that he often finds hard to make graspable for the people back home.

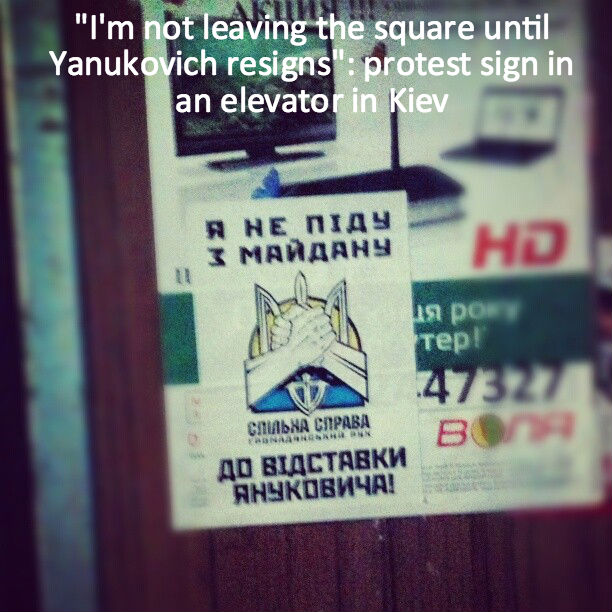

In the Russian language, there seems to be a proverb to shed light on all of life’s mundane phenomena, both big and small. One such proverb goes, “Your tongue will get you all the way to Kiev,” and surely enough, a couple of months ago, I found myself smack dab in the center of Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square). It was the day after President Yanukovich’s fateful decision to turn his back on an agreement that would have put Ukraine on the long but well-worn path toward European Union membership, and I just happened to be in the capital. As I stood on the Maidan and watched dozens of frustrated but optimistic protesters dance and sing, a canopy of EU and blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flags flapping in the late November wind and rain above their heads, I never would have guessed that I was witnessing the beginning of a revolution. Truth be told, it was my unspecific wanderlust and my interest in the Russian language that first got me, a university student from Texas, entertaining the idea of spending a year studying in Ukraine, but over almost half a year here, I’ve come to realize just how unique this country is, situated precariously on the fault line between Russian past and European future.

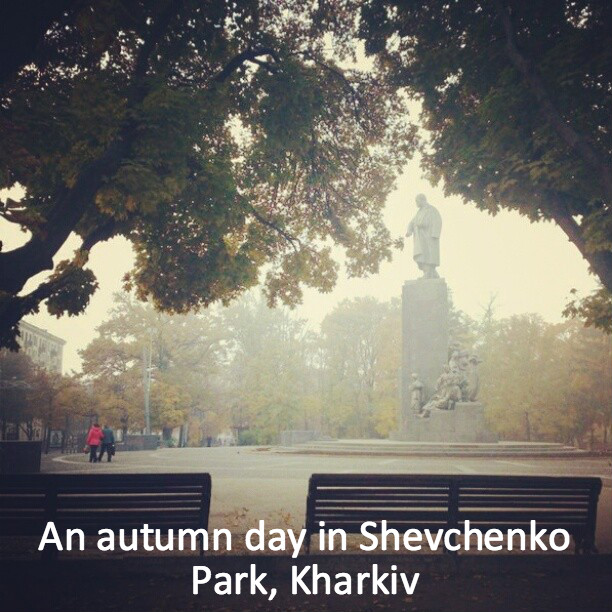

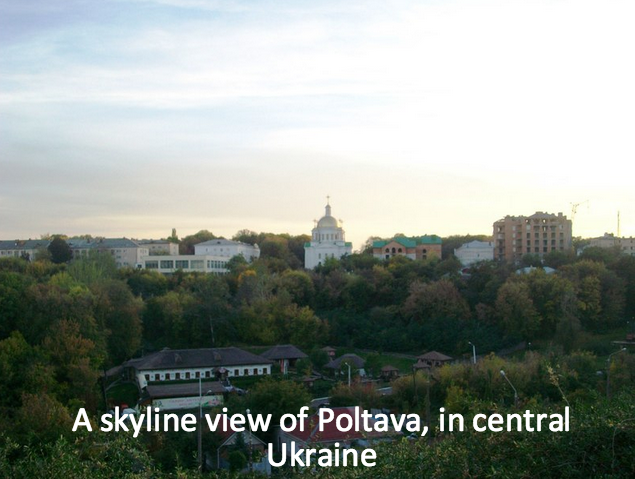

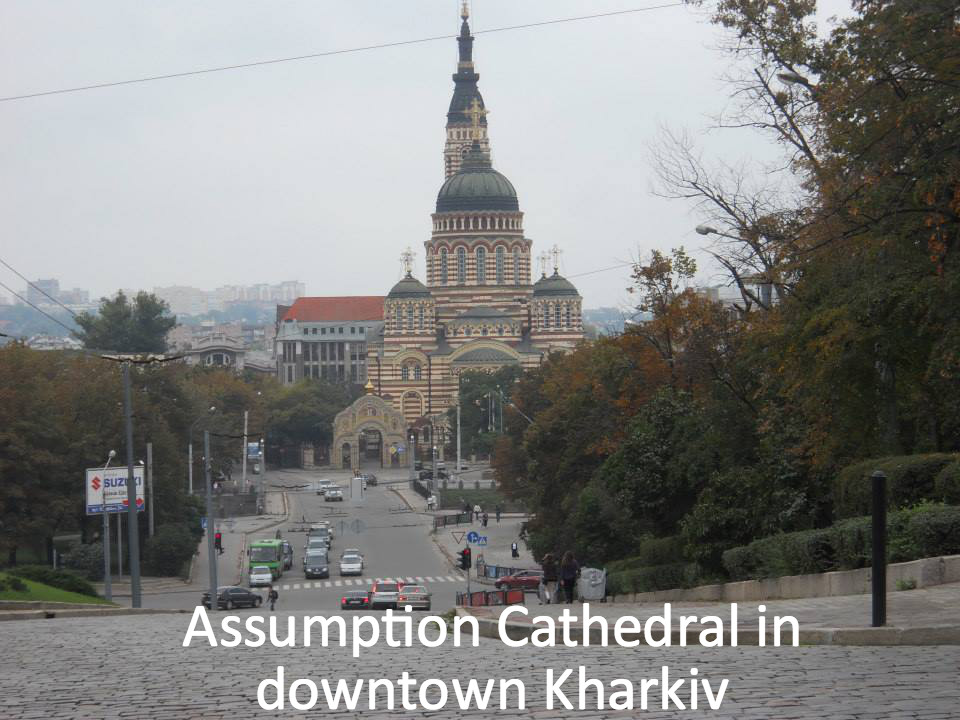

Modern-day Ukraine is basically the fusion of two historically, geographically, and linguistically distinct regions: the Ukrainian-speaking, European west, with its narrow cobblestone streets and Catholic churches, and the Russified, heavily industrial east. I study in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second-largest city, which is a short train ride away from the Russian city of Belgorod. It was the capital of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic until 1934 — even today, the city proudly bears the nickname of Ukraine’s first capital — and during Soviet times it was an important educational, cultural, and scientific center. If the eastern half of Ukraine has a capital, surely that title belongs to Kharkiv. The Ukrainian language is practically absent from daily life here. Stone-faced babushkas who’ve seen everything gossip with each other on park benches in Russian. University students breeze through dark, crowded corridors chatting in Russian. People in this part of Ukraine have friends, family, and business contacts in Russia and many cross the border on a regular basis.

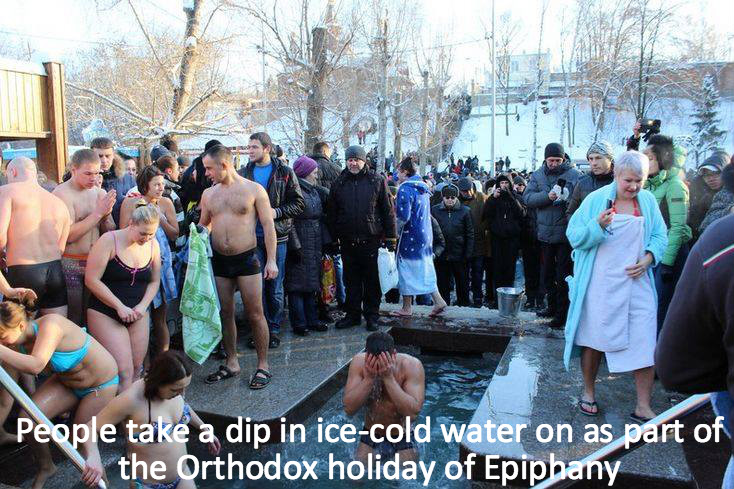

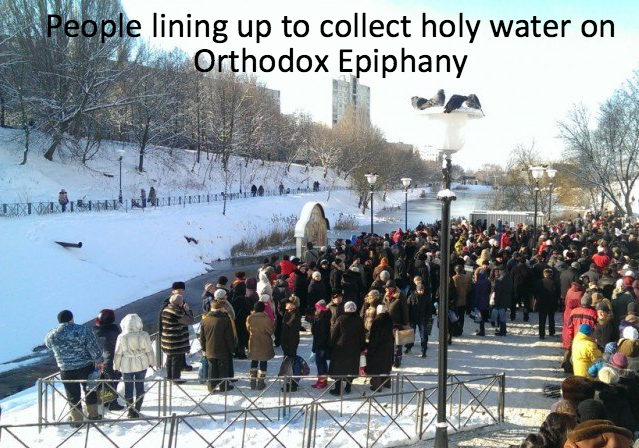

In fact, in moments of weakness, I’ve resorted to telling my friends and family that the place I live is “basically Russia,” because it’s so hard for me to create a picture for them of what life is like in Ukraine, a country that, frankly, most Americans couldn’t even spot on a map. To begin with, Ukraine is one of Europe’s poorest countries. Though Ukrainians are better off today than they were during the troubled times that followed the Soviet collapse, the pothole-ridden roads, crumbling apartment facades, and temperamental elevators that I encounter daily tell the story of the country’s present economic situation. But a visit to a Ukrainian home makes it clear that this is a country of people who value what they do have. Presentability seems to be a Ukrainian national trait. Whereas young Americans have no qualms about being seen tramping around town in basketball shorts, t-shirts, and sneakers, Ukrainians try to look fashionable any time they go out in public, women donning dresses and high heels and men showing off stylish jeans and polished, sharp-tipped black shoes. Whether at the farmer’s market, in the metro, or taking a walk in the park, Ukrainians seem to always look catwalk-ready. Ukrainians are just as selective about friends as they are about fashion; it can be hard to tap into a Ukrainian’s inner circle, but once you’re there, you’re likely to stay there. They have an unpretentiousness that an American might confuse with frigidity, smiles and laughter being reserved for occasions when they’re really warranted. The Orthodox Church is one of the strongest forces in society — just about every Ukrainian man wears a three-beamed cross necklace under his shirt; men and women of all ages cross themselves and bow as they pass onion-domed cathedrals on their way to work and school.

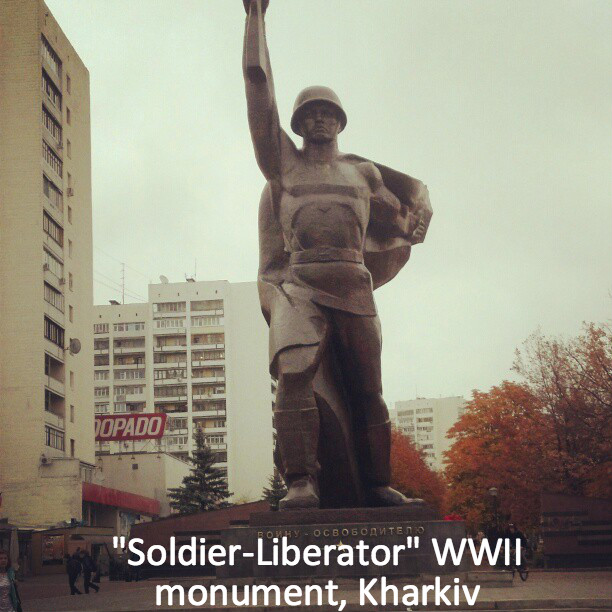

But maybe the biggest difference between American and Ukrainian culture is the Ukrainian collectivist mentality, cultivated over centuries of serfdom and then forced communal living under the Soviet regime. It’s a mentality that gives priority to the interests of “we” over the interests of “me.” Because of the extreme hardships that Ukraine endured during Soviet times (it was known as the “breadbasket of the Soviet Union”; in the 1930s millions died as a result of a man-made famine known as the Holodomor) many Ukrainians developed fiercely anti-Soviet and anti-Russian attitudes. Following World War II, however, the accelerated Russification of eastern and southern Ukraine gave rise to the fundamental split we see in Ukrainian society today.

That’s why most people in this neck of the woods have a wary, if not outright negative, attitude toward the battle unfolding in the streets of Kiev. They don’t sympathize with their western counterparts, who see a yawning cultural gulf between Ukrainians and Russians and feel animosity toward that country and its language. During the political tumult of the last few weeks, Kharkiv has been notably placid, its city square (the largest in Ukraine and one of the largest in Europe) empty on most days save for a towering Christmas tree and a holiday village complete with cottages, gigantic snowmen, and life-sized nesting dolls. And even with all the bloodshed that resulted after the approval of a package of controversial laws limiting the rights of Maidan protesters, the only sizeable demonstration in Kharkiv was a demonstration in support of the Yanukovich regime. Nevertheless, it is important not to fall prey to the idea that eastern Ukrainians perceive themselves as somehow less Ukrainian than their brothers and sisters across the Dnieper River. As a foreigner, it is it is difficult to understand all of the nuances of Ukraine’s east-west conflict, but I interpret the issue this way: Easterners don’t see the Russian language and Russian cultural influence as things that hinder the development of Ukrainian culture and statehood, while westerners want a clean break with the past, which involves ditching Big Brother Russia and forging a distinctly Ukrainian path.

It reminds me a bit of the generations-old north-south divide in the United States that separates the twanging, sweet-tea-sipping southerners from the busy, progressive, fast-talking Yankees of the north — effectively two nations, with drastically different conceptions of the past, present, and future, united (if at times grudgingly) under one flag. This country on Europe’s frontier already has a special place in my heart, and I sincerely hope that its people and its government will find a way out of these troubling times that gives Ukrainians of all stripes a reason to be proud to be not Europeans or Russians, but Ukrainians.